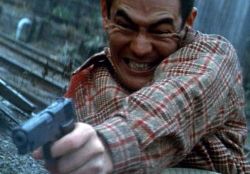

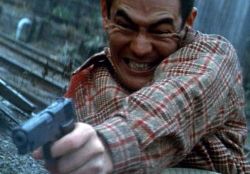

Violence is no fun. People don’t just fall down. They run away, struggle, fight back. Guns misfire. Hands shake on the trigger. In a massive brawl, you may not be able to tell who you’re hurting, or just what the fuck is going on at all. Japanese director Kinji Fukasaku conveyed all this brilliantly in his seminal yakuza (Japanese gangster) films of the 1970s. The phrase “shaky cam” had not yet been coined, but Fukasaku employed the technique as effectively as anyone. His employers at Toei Company favored hand-held camera work because it was fast and cheap, but Fukasaku used it for all the right reasons, just as he used freeze-frames, montages, and on-screen lettering to create a complex, enthralling, visceral experience that stayed brazenly enraged without ever alienating or boring its audience. He did so up until the day he died and he did so, in his heyday, making several films a year.

Fukasaku’s last film, Battle Royale (2000), did more than just prefigure an entire series of American YA novels and their popular cinematic spawn with vastly more intelligence, insight, and narrative economy; it provided filmgoers with one more righteously angry feature-length meditation on the subjects he spent his career exploring, institutionally sanctioned violence, societal hypocrisy, friendship, the true nature of integrity, and the fact that no matter what happens, no matter how tight the squeeze, no matter how hard they try to make you think otherwise, you always have a choice.

As a video store employee, I enthusiastically recommended Fukasaku’s Battles series, a multi-film portrayal of the decades-long struggle between yakuza gangs over Hiroshima in the wake of World War II that begins with 1973’s Battles Without Honor And Humanity. A customer I’d done so for returned to the store saying he wouldn’t watch beyond the first film because he felt he could tell by its finale where the series was going. The ending to which he referred portrayed protagonist Hirono Shozo (Bunta Sugawara) shooting up the Buddhist altar at his friend’s funeral to punctuate his implied threat to his treacherous gang boss that, “I still have bullets left.” Sounds like the setup to a standard revenge trip, but what that customer never found out is that the series doesn’t go there. Hirono stays yakazu and grows old following the rules, never rising above his station as a back-door peasant underboss. Boss Yamamori (Nobuo Kaneko) continues to grow rich off the backs of his men and the blood of young recruits without ever getting his hands dirty.

The world of Fukasaku’s films is not about noble outlaws seeking revenge, it’s about the way things work. We may be watching a film about gangsters, but we recognize the hypocrisy, injustice, and desperation, and we recognize that the characters who get the least respect in the context of a given story are the ones with the most integrity. These things are universal. The films provide a vicarious thrill in that they portray a time and place (Japan in the years following World War II) where fighting fiercely and brashly for your piece of the pie may actually get you somewhere, but it also might get you dead, horribly maimed, or swallowed up by the system. The “system” is represented by a modern society rising up out of the black markets and ashes of cities like Hiroshima and Tokyo, by the cops and prisons, and by the yakuza themselves, these last representing as rigid a society as ever there was. Prison time is not something that punishes specific perpetrators; it is a duty assigned to a gang’s most expendable members. Hits are almost unequivocally carried out by quivering young boys. The ancient Japanese rituals of loyalty, punishment, and contrition, though they leave behind their fair share of armless, handless, fingerless men, are revealed to be silk scarves on a greedy pig. And the modern society risen from the ashes ostracizes, shuns, and crushes the brash, ferocious fighters who laid its foundations.

These are the things that pissed Fukasaku off.

He managed to relate them to his film-going audience in a way that invigorates and, above all, entertains.

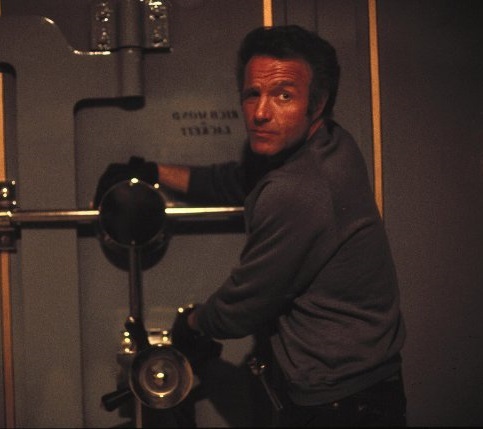

In the opening scene of Cops Vs. Thugs (1975), a swaggering Detective Kuno (Bunta Sugawara, who died last November at the age of 81) hassles a gang of kids in a car. He wears a leather coat, a scarf, and a hip-looking hat. After stealing the youths’ Zippo, shaking them down for money (ostensibly to pay the food vendor they just beat out of their sushi bill; Repo Man fans take note), and revealing that he knows who they represent, Kuno sends them off to bust heads with his blessing. We then launch into the opening credits, which roll over a montage of black-and-white photographs and Japanese calligraphy depicting the history of yakuza gangs in the city of Kurashima from 1945 until 1963, which is the year the movie starts. According to the on-screen type, it is based on real events. Over the next hour and forty minutes, we witness yakuza reporting each other to the police, yakuza drinking with police, drunken street brawls between yakuza and police, rapes, beatings, ultra-violent gang brawls, police brutality, and political corruption.

The core plot of the film involves a sort of passive-aggressive proxy war carried out by two factions of cops, each one representing a different yakuza group. Kuno is allied with the group led by underboss Hirotani (Hiroki Matsukata), whose boss is in prison until partway through the film. As viewers, we sympathize with Kuno’s faction, since we start the movie with Kuno, see Kuno vulnerable, and are exposed to Kuno’s unique brand of integrity. We also like Hirotani and his right hand Tsukahara (the hulking, distinctly visaged Hideo Murota) because despite being brutal, arrogant gangsters, they are brutal, arrogant gangsters right out in the open. Their enemies are manipulative, duplicitous, and sneaky; their play for power involves big oil and manipulates politics and public opinion.

At one point, Hirotani asks Kuno, “Who do we have to kill to solve this,” which in context is just sad. He and Tsukuhara don’t understand politics; they just want an honest fight. They are not going to get one. Kuno himself may be corrupt as all get-out, but he lives in a world that takes corruption for granted (Cops and its 1976 spiritual companion piece Yakuza Graveyard prefigure the character arc of a typical James Ellroy detective and are highly recommended to fans of that writer). He is a dirty cop who does not report the murderous yakuza who turns himself in to him both because he wants an up-and-coming yakuza in his pocket and because he is touched by the fact that the yakuza in question, who is in his apartment, is considerate enough to wash his own dishes after Kuno has fed him.

Morally complicated, just like real life.

Bunta Sugawara starred in countless Fukasaku films and communicated the rage, vitality, and warts-and-all humanity of Fukasaku’s vision with superior aplomb. His raw, honest performances, along with the films themselves, should put an end to all rumours that Japanese emotions are not capable of boiling over the edges of the pot of their reputedly repressed culture with more than enough tumult to snuff out the stove burner. In Cops, Battles, and Street Mobster (1972) Sugawara plays indignant, terrified, enraged, and disarmed. He plays a terrified recruit, a seasoned outlaw role model, and a brutal young hoodlum with equal authenticity. Though the ages of his characters in these films span decades, the films themselves were made over the course of a few years.

Like just about every film Fukasaku made during this highly productive period, Cops Vs. Thugs contains numerous memorable sequences, like the one in which Kuno and his partner demoralize a gang member using brutality, deception, and an unauthorized conjugal visit. This scene is driven by the brilliant theme music of Toshiaki Tsushima, as is much of the rest of the film, and plays like the last word in coercive persuasion. There is a “hit” scene played against the musical counterpoint of an absurdly optimistic, matronly anthem (“hello little one, you’ll have a big future, this happiness will last” intermingles with screaming, tearing, and stabbing), and the climactic siege, complete with tear gas grenades, that ends with the final demonstration of Kuno’s complex morality and a striking turn by Murota as Tsukuhara (according to Fukasaku, the siege scenario was inspired by real-life Japanese student protests taking place when the film was made).

In addition to lead actors like Bunta Sugawara, Tetsuya Watari (Yakuza Graveyard, Graveyard Of Honor), and Koji Tsuruta (Japan Organized Crime Boss, Sympathy For The Underdog), Fukasaku used many of the same actors in supporting roles, including the aforementioned Matsukata, Murota, and Kaneko. The presence of these actors, all quite accomplished, is a comfort and a thrill to anyone revisiting the director in an as-yet-unseen film. Fukasaku also cast Toei genre stars like Meiko Kaji (Yakuza Graveyard, Deadly Fight In Hiroshima), Sonny Chiba (Deadly Fight In Hiroshima), and Reiko Ike (Cops Vs. Thugs) in character roles into which they disappeared. It is easy to see why this director, though little known to Westerners outside of certain circles, is so highly respected in his native country. Battle Royale, Fukasaku’s last film (he died while in the process of directing its sequel, which was completed by his son Kenta), the adaptation of a 1996 novel set in a world where defiant teenagers are forced by the government to kill each other in a game, became one of Japan’s ten top-grossing films. It is a more than worthy bookend to a career that was all about fighting for each breath in a world that would deny us our right to do so.

– The Acolyte